India's Wild West

India's Wild West

Legend has it that much impressed by the prayers of a pious monk, a Jain teacher granted him the wish that when the monk opened his eyes, whatever he looked at would be consumed by flames. When the monk opened his eyes, the land in front of him became desiccated. He happened to be somewhere in Kutch. The local lore and belief is that this is what happened - the land continues to burn once a year as a consequence of the wish granted to this monk, only to resurrect and become a grassland after the rains, year after year. There are many variants to this tale and nothing really adds up, but a place with folktales has much to offer.

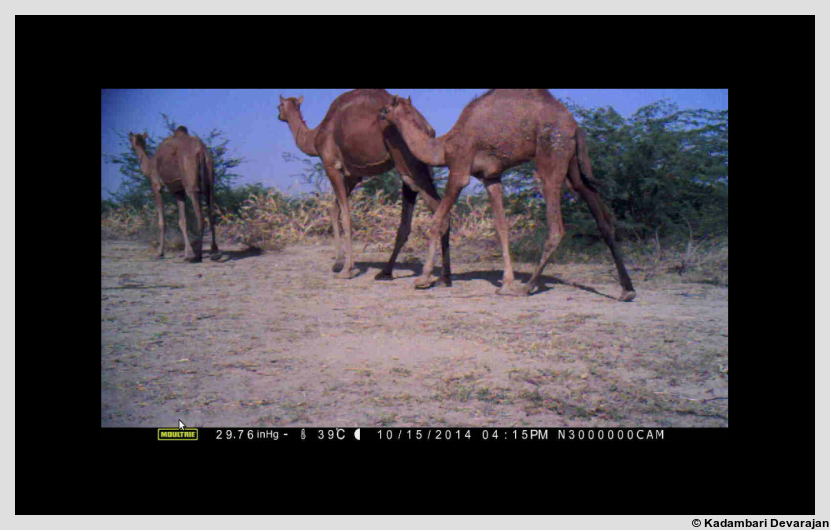

A herd of camels at Chari Dandh Wetland Reserve

With an area of more than 40,000 sq. kms., Kutch is unquestionably the largest district in India. It is in the north-western part of the state of Gujarat in India, and beyond the upper borders of the state is the country of Pakistan. The land, its people, and their culture are shaped and moulded by the extremities of the area and the climate.

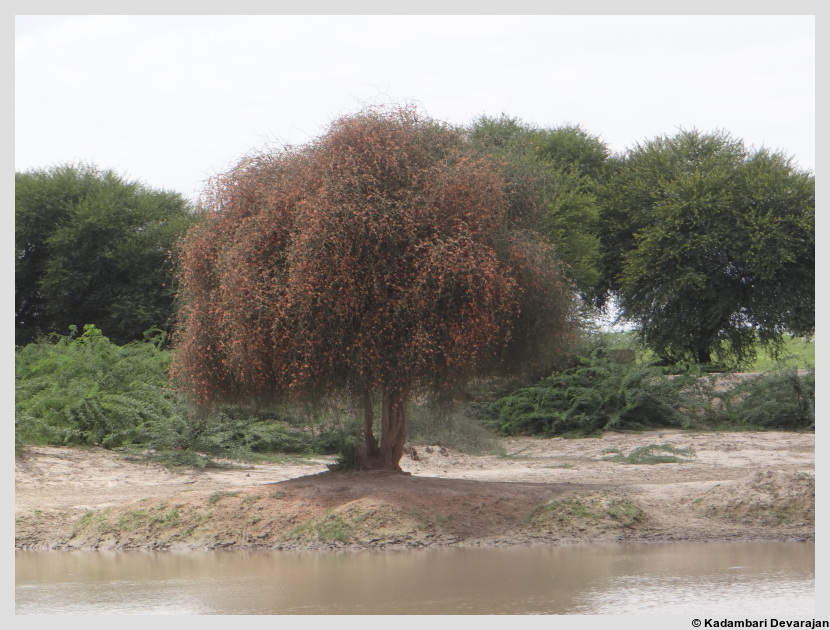

A grove of Acacia and Caparis trees

They lie at the confluence of different cultures and these influences exist today for all to see, in the clothes, traditions, food, lives, and beliefs of the people. It is a unique landscape, for where else in the world can you find a desert ecosystem with three distinct seasons (summer, monsoon, and winter), pockets of which transform into wetlands for a third of a year, is almost an island surrounded by two Gulfs and a salt desert, and for a few months in a year metamorphoses into the largest grassland in Asia.

Two sociable lapwings, from a group of five, in a grassy patch

It has a number of ‘Ranns’ which are shallow wetlands that dry up completely in summer and are submerged in water during and after the monsoons. The most famous and largest of these are the Little and Greater Ranns of Kutch. Its unique location and habitats have resulted in unusual faunal and floral compositions, that are superbly adapted to the extremities of the region. The location also makes it a pitstop and destination for an enormous diversity of migrant birds in winter. I live and work in this fascinating region as part of my dissertation fieldwork. Based out of the RAMBLE fieldstation in Hodka village, I set up camera traps and trackplots in the Banni grasslands of Kutch everyday to see what wildlife we can find here, with a focus on carnivores. My thesis research at NCBS is on the distribution and landscape use of multiple sympatric canids under the guidance of Abi Tamim Vanak and Vishwesha Guttal.

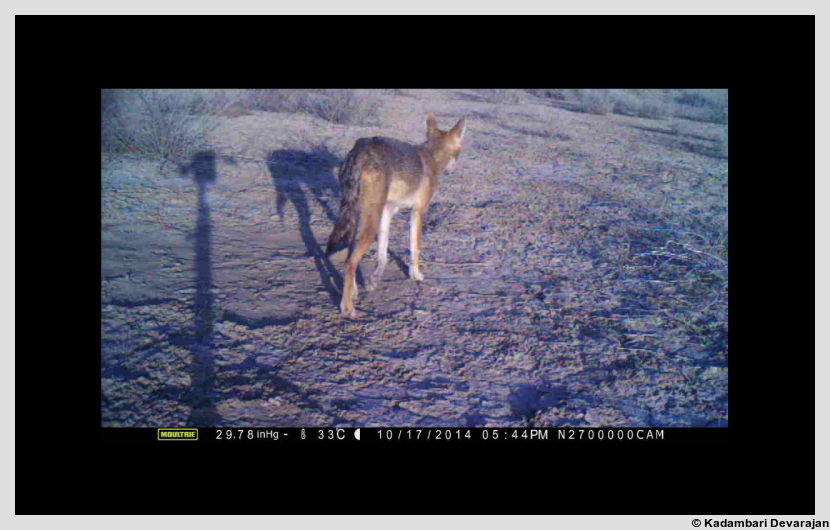

Jackals give me company almost everyday!

It is hard to imagine such an arid area being rich in biodiversity but it is surprisingly chock-full of organisms. While it may be hard to compete with a rainforest in terms of biomass, acre for acre, deserts do have their own unique faunal and floral compositions, and communities and assemblages of organisms that are superbly adapted to the arid conditions. Cold and hot deserts around the world are special places to see evolution in action. The desert is a lesson on adaptation and the resilience of life, and none more so than the arid landscapes of Kutch. To add to this, Kutch is a mosaic of arid and semi-arid areas, including seasonal grasslands. The vast open plains are amphitheatres for the marauding wolves, jackals, hyenas and foxes. The sand dunes and salt pans are odes to the complexity of life forms. The grasslands are lessons on the fragility and interactivity of natural systems

Indian wild ass at LRK

The area is surprisingly rich in biodiversity. There are a host of mammals, birds, and reptiles that can be commonly seen throughout the countryside. Ecologically speaking, the Little Rann of Kutch's claim to fame is the Indian Wild Ass Sanctuary, arguably the largest sanctuary in India. It is one of the last vestiges of the Indian wild ass, an endangered subspecies of the onager or the Asiatic wild ass. During the monsoon, when the entire area gets submerged, these wild asses move to the countably many islands with elevated ground, known as bets. After a few showers, it was very dangerous driving through this transformed land and a unique experience seeing it metamorphose from dry, parched, salty, white desert one day to sludge the next from overnight rain.

A baby long-eared hedgehog

An Indian hedgehog from one of the cameras I set up in October 2014 in Banni

Black-naped hare in a camera trap I had set up

A common grey mongoose at Narayan Sarovar Chinkara Sanctuary

The other mammals that can be found in the region include the nilgai, blackbuck, chinkara, wild boar, black-naped hare, desert fox, Indian fox, Indian wolf, golden jackal, striped hyena, Indian grey mongoose, small Indian mongoose, porcupine, Indian or pale hedgehog, Indian long-eared or collared hedgehog, caracal, desert cat, jungle cat, rusty spotted cat, Asiatic wildcat, leopard, common palm civet, small Indian civet, and honey badger.

One of the camera traps set near the village of Sadai had a video of this jungle cat scent marking

This region has a diverse assemblage of carnivores and arguably the highest canid diversity in the world, with the golden jackal, Indian fox, desert fox, and Indian wolf. This astonishing community array is made larger when domestic dogs are considered. Interestingly, the villagers frequently feed the jackals in addition to the already human-subsidized dogs. The felids are not far behind – with at least five species found throughout the region, namely the caracal, jungle cat, desert cat, rusty spotted cat, and leopards. To add to these, there is a healthy population of striped hyenas scattered along the region. This makes these arid lands excellent natural laboratories to study interactions among carnivores.

This is from a very cute jackal video I got in one of the camera traps set near Bhirandiyara.

Here the jackal approaches the camera after checking the shadow out.

We can see from the shadow that the jackal is nibbling at the camera trap.

The jackal gives up on trying to eat the camera trap and just leaves.

The golden jackal is quite slender and one can hear them howling in the evenings. They are about the size of a mongrel dog but thinner and with a narrower muzzle. They have piercing honey-colored eyes. The jackal here seems to be highly variable in size and coloration. But for most part, the coloration seems to be a rufous-mixed-with-brown belly and body with a black back. Alongside these solitary canids of which healthy populations are found here, the Indian wolf is also a predator to be reckoned with. With no dearth for vast open plains that are the preferred habitat of wolves, Kutch offers the perfect home for these packs.

A jackal a day ...

A jackal already donning its winter coat in early September 2014

As is true with any region with an interesting culture and history, Kutch too has a number of folktales involving the animals found here. Considering that Kutch has been a melting pot of cultures and traditions, and from my interactions with the people of the area, I think the region has a rich oral history that is waiting to be explored.

An Indian fox on the run

An Indian fox from a camera set in Banni in October 2014

As a sampler, this quest for folktales has already thrown up some interesting stories, and much to my delight, these feature canids as the protagonists! Take the instance of the fox. Locals consider the fox (laukdi in Kutchi, the regional language) to be wily and clever and quite capable of deception in the face of danger, quite similar to many other cultures. The story goes that foxes escape from tricky situations with simply a swish of their bushy tail. They are also thought to be quite proud. Such is their pride that come winter and the male fox is forced to walk on three legs, lest the earth is unable to bear the full weight of the proud fox.

A desert fox in eastern Banni

A desert fox from a camera trap I had set near Dumado in the summer of 2013

Incidentally, Kutch is unique in India and is one of the few places on earth where there are two species of foxes co-existing. Between the desert (or white-footed) fox and the Indian fox, the former is bigger and has prominently large ears - an adaptation to the hot desert conditions. It is also more lightly colored than the Indian Fox which has variable coloration since it has a larger distribution across India while the desert fox is restricted to these parts.

A male nilgai near Udhmo village

A female nilgai in Naliya

Similarly, the herbivores are not far behind in terms of diversity. In addition to the wild ass, ungulates such as the nilgai, blackbuck and chinkara can be found in Kutch. The chinkara is an elegant and delicate-looking gazelle found in these parts. It is a light tan or buff in color with some dark chestnut or brown-black and white stripes on the face, running from near the ears to the muzzle and a pair of slender horns starting just above the eyes, and before the ears.

A desert gerbil in the bush

A desert gerbil ready to scoot into its burrow

Two types of gerbils can be found here - the Indian and the desert. Eastern Banni is usually teeming with desert gerbils, with large pockets pockmarked with gerbil burrows. Just a few minutes of patience will be rewarded with the Jack-in-the-box popping of tiny faces, that keep shifting. This dance of the rodents is quite surreal, and feels like the sands below your feet are shifting.

A spiny-tailed lizard mother with babies taken in the summer of 2013

A spiny-tailed lizard that is frequently seen from the fieldstation's kitchen window

Spiny-tailed lizard feeding

The longest saw-scaled viper I have ever seen! This was near the village of Shervo in Banni.

Indian flap-shell turtle near Bhuj

Reptiles that can commonly be seen in the region include the Indian monitor, desert monitor and spiny-tailed lizard, apart from a variety of snakes. The spiny-tailed lizard is endemic to the region and is unusual since its diet is predominantly herbivorous. They dwell in burrows in the ground, in clusters or colonies, and hence are more common on firm ground than sandy areas. They can frequently be seen basking in the sun, but are usually shy and scuttle to the safety of their burrows when danger is imminent, such as when predators are in the vicinity.

A sociable lapwing

Two male great Indian bustards in an agricultural field near Naliya in early October 2014, just a few weeks before Cyclone Nilofar

A cream-colored courser

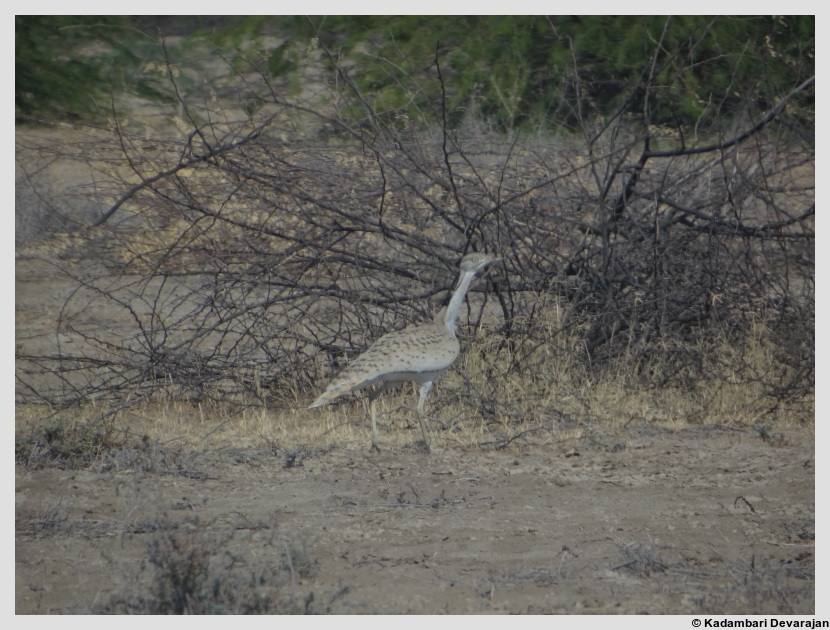

A MacQueen's bustard

Male chestnut-bellied sandgrouse

Female chestnut-bellied sandgrouse

Avifauna that the region is famous for include the Macqueen’s and great Indian bustards, sociable lapwing, greater short-toed lark, lesser florican, different wheatears (desert, variable, Isabelline, and red-tailed - the last being rather rare), Saker and Laggar falcons, and short-eared owl. The region is said to contain some 300 species of birds, including visitors.

A juvenile greater flamingo near Naliya

A mixed flock of common and Demoiselle's cranes in Banni

Black-necked storks in flight near Naliya

Common cranes

Kutch is also a popular breeding ground for greater and lesser flamingoes. The water holes and salt lakes turn into flamingo cities, a riot of pink against a white, shimmering landscape. The grasslands teem with larks and wheatears, that flit about between the blades of grass.

A Eurasian griffon - vulture sighting have become quite rare in an area that was earlier teeming with them!

Pallid harrier

A silverbill at Hodka village in Banni

A common kestrel near Naliya in early October 2014

A steppe eagle feeding on a black-naped hare on a rare foggy day in October 2014

A long-legged buzzard

A juvenile Egyptian vulture

A nightjar

Come winter, and the birds of prey take over bushes and shrubs. Kites and falcons, eagles and harriers take over any woody vegetation persisting in the dry conditions. Ducks and cranes, waterbirds and waders have a choice of pitstops across the many ponds and lakes that dot their migratory routes.

A herd of camels on a camera trap I had set up

Life in the desert may be hard, harsh, and demanding – but no less beautiful, diverse, or complex than in a rainforest. These arid systems along with grasslands are under threat from different directions. They are frequently considered wastelands and cleared to make way for development, without thought to the communities of organisms that have made these arid and semi-arid regions their home and way of life.

A shepherd with his sheep in a grassland near Gugurdui

How the organisms interact with their environments and among themselves is crucial, interesting, and essential to the conservation of the organisms as well as the landscapes. Complete destruction of their habitat could disrupt any chances of conserving a species. This is true of many species, including the bustards that are on the brink of extinction. These habitats are on the verge of disappearing and urgent action is necessary to save them as well as the numerous species under their aegis.