The Trials of Trail Life

The Trials of Trail Life

"Ecology isn't rocket science. It's much more difficult!" - Steve Carpenter

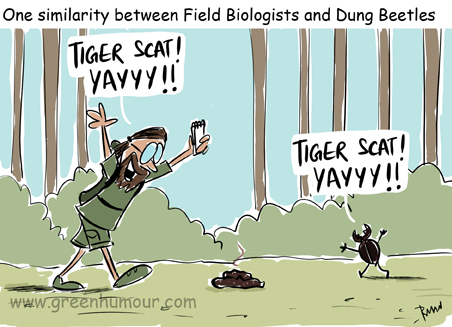

I've been told many times over that I have a "bad-ass job". Isn't field research all about traveling to exotic parts of the planet, exploring spectacular wilderness areas, encountering the coolest organisms, and just basking in the glory of the natural world? It is, and I love what I do! But like the Bob Dylan song goes, "most of the time", it isn't. One has to put up with not having creature comforts for extended periods of time, frequently making do without even (what most would consider) basic necessities or amenities (imagine no phone or internet connectivity for weeks together, and you can forget hot water!), being away from family and friends, and dealing with field situations ain't always smooth-sailing.

All the grunt work goes on behind the scenes and believe me, it's not glamorous at all. Scenario 1: Bushwhacking, while on foot, trudging along in a rainforest that lives upto its name, during the monsoon, being scratched and bloodied by the undergrowth. Leeches start crawling up your body when you "stopped for ten bloody seconds" to just take a measurement or do a point count, moving with a GPS device and hoping not to get lost. Clambering up rocks slippery with moss while being drenched to the bone, wading through forest streams, and simultaneously being wary of the jungle's elephants, bears, leopards, and snakes. The last thing you want is to be bitten by a snake or come down with malaria - the nearest medical help is miles away.

Scenario 2: Setting out camera traps, in the desert, just as summer is transitioning into the monsoon. The temperature is a soaring 50 degrees Celsius and you're positively roasting in the heat. Your relief that things may cool down a bit with the first rains is shortlived, dreams of collecting data better once the rains come lay shattered. The entire desert transforms into sludge making navigation impossible, and the question "oh shucks, how on earth are we going to retrieve the camera traps that were painstakingly set out just last week?" haunts you in your dreams. You're reminded of this reality with every turn of the wheel, the 4WD roaring and splattering mud in all directions, successfully going nowhere. And, oh, there's no phone connectivity and help seems miles away. Nobody even knows where you are! Aaarrrrgh!

Scenario 3: Climbing perilous mountain rocks, freezing in the snow, in your first field season up in the mountains, recovering from altitude sickness. You lay out your quadrats for taking some vegetation measurements and look out for herbivores along the cliffs, while managing that dreadful nose which keeps spewing blood every so often. Your last bath was a month ago and you lap up your meals at the village hut, warming yourself by the fire, and taking notes by candlelight. Electricity, telephones, and the internet seem a lifetime away. How the hell is one supposed to write notes, collect data, and do research without electricity? Well, as long as you're one step ahead of frostbite!

Scenario 4: Scuba diving to collect data on a bleached reef, keeping in mind the expenses involved with each dive, and the ridiculously expensive equipment, and thinking of ingenious ways to collect and record data underwater. There's the possibility of not surfacing with enough data for the study, and the pressure of planning out each dive in addition to being wary of the surroundings - jelly-fish and sharks and sting rays provide not just entertainment, you know! You have to time your dive carefully. And if you're the woebegone researcher who is also that wee bit careful about personal hygiene, then good luck to you. Imagine answering nature's call, in a dive suit, in the middle of collecting data, with a dive buddy watching. The only thing worse is to do the above while throwing up!

You get the drift. Apart from being logistical nightmares to plan, fieldwork brings with it a slew of challenges and difficulties - being able to eat what's available, adapt to living at a field station or living it out alone at a camp or sharing a villager's home, acclimitizing to life in remote areas, and a plethora of other idiosyncracies that crop up in the field.

If it weren't that fieldwork is as incredibly rewarding and wonderfully interesting as it usually is, field biologists would be a dying breed. That they still are is another story. The bottomline is that: field research is tough. Every field site has a unique combination of things you will love and hate about it - maybe the wildlife found there, the living conditions, weather and the environment, or even the people you associate with. Frequently, molehills become mountains, minor problems blow out of proportion - just because. What might seem a trivial problem in say a city, might seem catastrophic at the field site. And people have a tendency to become grumpy and annoyed easily in tough field conditions.

Different people react differently too. And there are phases that everyone goes through. It is not unusual to quickly progress from denial to anger to indifference to a beatific calmness, all during the course of a single field season. Sometimes minor irritants, like the mosquitoes or the ticks or the leeches, or a futile attempt at taking some measurements, or an arduous exercise spent arguing with associated people, or malfunctioning or stolen equipment, could affect your work and mood. And, this is what segregates the difficult from the challenging. For in such cases, life is not just challenges that are overcome with the ensuing sense of accomplishment, but is actually difficult, in the form of annoyances, that need to be dealt with. What I'm trying to say is that, challenges typically tend to eventually become adventures, anecdotes, and field stories, while the difficulties and annoyances end up making life miserable. For a short while, but still.

The challenges keep us researchers on our toes. Of course, the difficulties we would love to live without, thank you. That said, would I give up field work for a comfy life? Not a chance. In fact, it went the other way for me. I would still rather deal with field work, and the trail of creepy-crawlies, bad food, and sleeping bags that follow it, to the monotony of a metropolis and the cushy comforts of an armchair! Besides, the perks and incidental benefits are too good to be true!