Desert Dynamics

Desert Dynamics

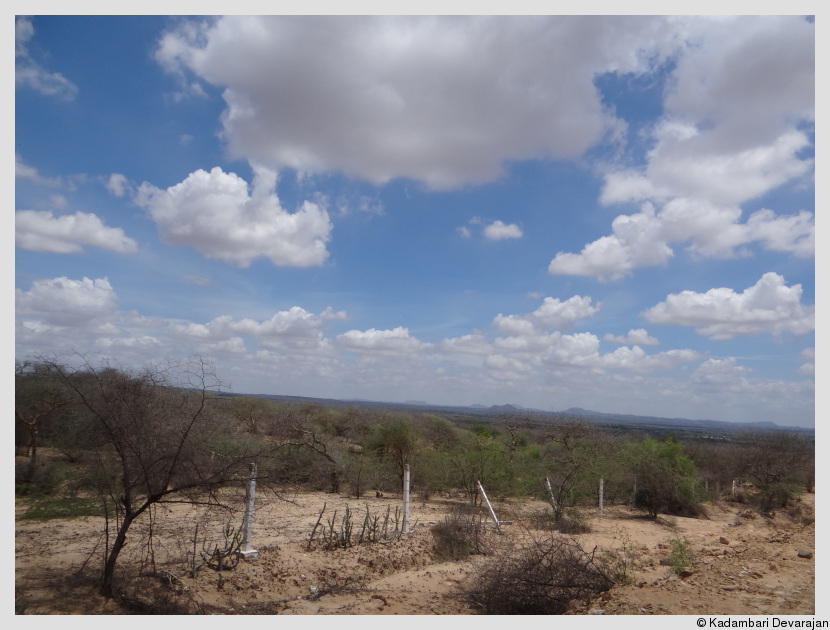

With an area of more than 40,000 sq. kms., Kutch is unquestionably the largest district in India. It is in the north-western part of the state of Gujarat in India, and beyond the upper borders of the state is the country of Pakistan. The land, its people, and their culture are shaped and moulded by the extremities of the area and the climate. They lie at the confluence of different cultures and these influences exist today for all to see, in the clothes, traditions, food, lives, and beliefs of the people. It is a unique landscape for where else in the world can you find a desert ecosystem with three distinct seasons (summer, monsoon, and winter), pockets of which transform into wetlands for a third of a year, is pretty much an island surrounded by two Gulfs and a salt desert, and for a few months in a year metamorphoses into the largest grassland in Asia.

Desert sunset

It has a number of 'Ranns' which are shallow wetlands that dry up completely in summer and are completely submerged in water during and after the monsoons. The most famous and largest of these are the Little and Greater Ranns of Kutch. Its unique location and habitats have resulted in unusual faunal and floral compositions, that are superbly adapted to the extremities of the region. The location also makes it a pitstop and destination for an enormous diversity of migrant birds in winter. My last visit to the region was for some birdwatching in the Little Rann of Kutch two years ago. If I enjoyed myself then, after this visit I was truly enchanted - I cannot wait to return for longer and work in the area soon.

I had the opportunity to live and work in this fascinating region for a short span of two weeks. I was to set up camera traps and trackplots in the Banni grasslands everyday to see what wildlife we could find here, with a focus on small carnivores. I was working here as part of the RAMBLE (Research and Monitoring in the Banni LandscapE) project and was funded by this. The RAMBLE field station is being constructed in the village of Hodka some 70 km from the city of Bhuj. The project is an initiative involving a number of local NGOs (Sahjeevan, KLINK, etc.), and research institutions (NCBS and ATREE) hoping to increase research on the floral and faunal biodiversity of the region.

At the RAMBLE field station

There are already a few social science sub-projects on the anvil at RAMBLE. They have selected 100 grids across the region which are going to be made into permanent plots. I shortlisted (with a lot of help) grids from the 100 that were not too far from the field station to set up camera traps and track plots. I landed up at Hodka just as summer was ending and temperatures were soaring. A week into the trip, my best laid plans needed a raincheck (pun unintended!) with the early onset of the monsoon. This is a compilation of my experiences and observations over the trip. I am extremely grateful to Dr. Abi Tamim Vanak (ATREE), Dr. Pankaj Joshi (Sahjeevan), Ameya Gode and Chintan Sheth (ATREE), Anil Gohil (Sahjeevan), Rasul Bhai and Mutthalib Bhai (the field assistants), Premji Bhai and his family at the Hodka homestay, everyone at Sahjeevan, and all those I interacted with in Hodka and other villages. This trip would not have been possible without them.

Band of brothers - Premji Bhai and his brothers with Rasul Bhai and Mutthalib Bhai

Life and Landscape

Legend has it that much impressed by the prayers of a pious Jain monk, a Jain teacher granted him the wish (unasked) that when the monk opened his eyes, whatever he looked at would be consumed by flames. When the monk opened his eyes, the land in front of him became desiccated. He happened to be somewhere in Banni. The local lore and belief is that this is what happened - the land continues to burn once a year as a consequence of the wish granted to this monk, only to resurrect and become a grassland after the rains, year after year. There are many variants to this tale and nothing really adds up, but a place with folktales has much to offer.

This place has a history of pastoralism that is apparently 450 years old. I find this landscape, the people, wildlife, and culture to be incredibly fascinating. For one, the pastoralism is unlike anything I have seen or heard of before. The livestock graze by themselves, they leave in the night and return in the morning to the same place to be milked, all of their own accord.

Some livestock near the village of Bhirandiyara

I asked Premji Bhai of Hodka village how this happens. He gave the following example in reply - he said that he got a young buffalo from his wife's father this month. When they acquire a new one, they themselves feed it and keep it separately for the first few days. Then, they introduce it to the rest of the herd and leave it there. It will start following the herd and learn to go wherever the herd goes. Soon it will also automatically come every morning to be milked.

Some goats

I also see many goatherds around, near field sites. The goats here seem to have a characteristic white body and black head. The goatherd carries a can wrapped in a wet rag sack filled with water on one side of his stick and a leather (goat-skin?) bag filled with milk or water hung on the other side. He carries this stick on his shoulders.

The livestock here seem different in different places, with personalities to match. There are the buffalo which all look alike to me - granite grey and huge, and hell bent on knocking down my camera traps when they see one. If they get an itch, they use the camera trap as a scratching post, much to my chagrin! The camera trap in grid 32 had been battered a couple of nights ago - I don't know how they managed it but had broken the camera off the mount (where it had been screwed in). Thankfully the damage was not irreparable - we managed to fix this but were careful to move it to a less obvious location a few metres away and along a smaller track near the Prosopis and hidden by it. We can also see some horses and domesticated asses browsing near village huts, as well as camels elsewhere.

A camel

In most of the villages, the locals live in round cottages made of mud and are called 'bungas'. The interiors are painted in lovely colors (mud-based) and the artistry is impressive. They also use a form of art called 'mud work' and form patterns using clay that are then painted over. Small pieces of decorative mirrors stuck for effect. The household is kept immaculately clean, from what I saw.

The bunga where I stayed

Inside the bunga - my gorgeous, village home for a few days

It had been overcast the whole day. The heat was scorching and unbearable. I did not know whether to be relieved or apprehensive when it started raining late in the afternoon that day. The rains would undoubtably ease the scorching temperatures and make life more bearable, but then the rains could also spell doom for the track plots. Anyway, we had finished the work planned for the day surprisingly early and I was back at the bunga well before sunset for once. The folks there got out all the handicrafts they were famous for and started displaying their wares.

An overcast sky at Hodka village and ... rain!

Women busy at work with their needles - one eye on the baby on the 'khatiya' or cot

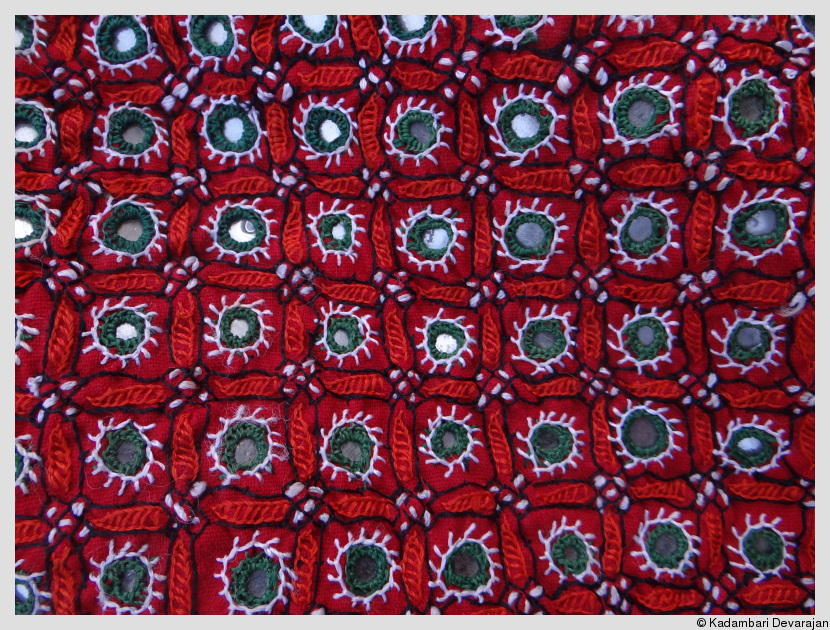

I ended up buying a lovely and small quilt with some 'cut work' which takes roughly 10-15 days to make (the patchwork was machine stitched by Meghji Bhai with the embroidery done by hand by Baya Bai - his mom), a beautiful and multi-colored table runner of sorts with mirror work and embroidery made by Baya Bai, three patchwork bags that Meghji Bhai stitched, some jewellery that Mori Bhen ('behen', the sister) made by hand (a 'jirmer' made of color beads and a 'kanta' with metal overlaid with some some small cockle shells, I think). The women then brought out their traditional clothes and dressed me up - they even taught me how to hold the odni and had the girls working here with Sahjeevan take photographs. Beautiful as the clothes were, I did not buy any thinking I would look incongruous no matter what the circumstance!

Baya Bai working on some embroidery

Beautiful and intricate mirror work

The children wear 'ghagra-cholis' (skirt-top) with the choli having a longish front part full of embroidery, mirror work, cockle shells and what-not. The women wear backless tunics called 'kanchda' that have intricate handwork including colorful embroidery ('kutch work') and mirrors. The tunics are worn over pleated skirts or ghaghras with a string around the waist to adjust. They wear a colorful 'odni' which they pull over their heads when there are men around or when they are being photographed. The white bangles that they wear near the upper arm are called 'choodas' and girls start wearing them around when they are around ten years old and come of age. They also wear a lot of colorful bangles from their wrist to their elbow which these women brought from Bhuj and these are called 'kangan'. I think only married women wear backless tunics while unmarried girls wear ghagras with the odni and children wear just the ghaghras.

The affectionate grandma - Baya Bai with her 4-month old granddaughter

A Kutchi woman with some of her handicraft

Bayambai, the mother, is famous for her handicrafts. She has apparently traveled to France for a mela and has gone to Sind in Pakistan thrice, sponsored by the government. I think that is quite an achievement for these women who are not even allowed to talk to other men.

A stitch in time ...

The children liked being photographed and at first demanded money ('paisa de') - apparently foreign tourists would take pictures of them and hand them some money and so ... After a while, they started asking to be photographed and would pose for me. They are a cute lot and with ten children around, life is interesting and cheerful.

Displaying their wares ...

Earlier, they showed me albums with photos of Amitabh Bacchan's visit for Gujarat tourism's 'Kutch nahin dekha, to kuch nahin dekha' (if you haven't seen Kutch, you have seen nothing yet) ad campaigns. He had visited them here at the bungas and one of the ads has Baya Bai doing some embroidery sitting outside the fifth guest bunga. He then went to what they call the White Rann for some filming and has taken pics with the entire family. He had apparently visited twice and it is a matter of pride for the family - they are now local celebrities of sorts :)

Mori Ben's nimble fingers at work

One of the most memorable encounters that I had during the trip was my first meeting with Pandhi Kaka. He reminded me of the Kabuliwala from Tagore's story of the same name. He is seemed well-known in the village and highly respected. He was very knowledgable and pointed out some spiny-tailed lizards whenever I visited the field station.

Pandhi kaka at the RAMBLE field station

The similarities between the landscape, the fauna, the people, cultures, colors, attitudes, and cultures here and in parts of Africa are uncanny. However, a majority of the people here (like in the rest of Gujarat) are vegetarian. The villagers are very tolerant of the different creatures and are very knowledgable about the different species. They are very warm people and would talk to me at length about everything. I would frequently be invited to their homes for tea or food - their generosity is amazing! Wherever we stopped, I would have people asking me about my work and what wildlife I had seen that day. They had local names for many species and I learnt to question them about these by initially describing the animal and noting down their name for it.

Food

The people of Kutch eat spicier food than the rest of Gujarat - which means they use little or no sugar when cooking their dishes, just the way I like it. The downside is, they are not very fussy about their sweetmeats. The average Gujarati has a sweet-tooth and indulges at every meal. This is not the case with the Kutchi. That said, the region is most famous for its milk sweets - not very surprising considering the amount of milk that these people produce. Everything is cooked in ghee and just melts in the mouth. They keep cool in the desert by having cool buttermilk from earthen pots. I think buttermilk is the only reason my brain didn't melt!

A typical Gujarathi thali at a lunch-home in Bhuj

The women milk the cows every morning and churn fresh butter everyday which they use for cooking. The people have copious amounts of hot, milky 'chai' or tea throughout the day! The field assistants would stop somewhere for some hot chai every so often - if they found my avoidance of the milky tea strange, they kept it to themselves. The most famous sweet of the region is a milk-based treat called Mawa. The locals claim that what you get in the shops is 'adulterated' with biscuits - the best mawa is homemade with fresh milk and sugar.

The milk sweet Mawa

Scrumptious Khara lola for breakfast

Breakfast is typically either a flat bread of some kind or pauva (rice flakes) which is the Gujarati name for poha. My favorite meal from here is the khara lola which is a roti with spices and a lot of onions mixed into the dough. This is served with a kind of homemade cream cheese or clotted cream and no pickles since it is quite spicy by itself. Then there is the koki, which is to the Sindhi household what parathas are to the Punjabi. It is different from a paratha in that cumin, miscellaneous spices, onion, and chillies are added to the dough which is then split into balls and rolled whereas a paratha is stuffed. It is served to you dripping with ghee - every bite is sinful and just melts in the mouth. It is served with hung curd and pickle.

A typical Kutchi lunch

Lunch would be a thick roti made of wheat or bajra, a dal (spicy lentil stew), plain rice, and some subzi (or vegetable, typically a tuber or root vegetable). The Kutchi diet is heavy on potatoes (since most other veggies are hard to come by), lentils, milk, and milk-products. Dinner would be a variation of the lunch with khichdi instead of plain rice. Khichdi is simply rice cooked with lentils. It is had with a big dollop of ghee. The leftovers are mixed with buttermilk and typically eaten for breakfast the following morning.

Wildlife

I have managed to see a jackal or two almost everyday. The first evening here resulted in a phenomenal four jackals in under ten minutes, near Hodka. The jackal here seems to be highly variable in size and coloration. But for most part, the coloration seems to be a rufous-mixed-with-brown belly and body with a black back, rather like the black-backed jackal in sub-Saharan Africa but with less prominant black and much larger, I think.

A jackal

The golden jackal is quite slender and you can hear them howling in the evenings. I estimate that it is about the size of a mongrel dog but is thinner and with a narrower muzzle. They have piercing honey-colored eyes and look right at you. They sprint when they see people but stop near some cover (mostly Prosopis), parallel to the position of the person, turn and look right into your eyes. Sometimes, they just pause and run away, while at other times they move away much more slowly, occasionally pausing every so often and checking to see where you are.

The desert or white-footed Fox, from a camera trap I had sent in the Rann near Dumado village

Between the desert (or white-footed) fox ('booey') and the Indian fox ('laukdi'), the former is bigger and has prominently large ears - an adaptation to the hot desert conditions. I think it is also more lightly colored than the Indian Fox which might also have variable coloration considering that this has a larger distribution across India while the desert fox is restricted to these parts. I have seen four species of foxes in two weeks now - the desert fox and Indian fox here, as well as the Patagonian fox and the Feugian fox in Argentina. The last is much bigger than the rest, and plumper. The Patagonian fox might be the same size as the Indian fox, but I'm not sure.

An Indian gray mongoose

Meghji Bhai's anecdote

When asked about the animals I saw on a day, I mentioned that I saw a noriya. Meghji Bhai promptly said, "Mongoose!" I was surprised since they didn't know that seeyad is Jackal in English. The locals have an impressive knowledge of the fauna here but know only the local names and not the English ones. This being the case, I was taken aback by his exclamatory 'Mongoose'. He laughed at my surprise and started narrating a story. He said, "My grandfather's name is Mangu and when he was alive, he used to live beyond that fifth bunga there. A lady from abroad was staying here for a few days. One day when sitting here (the dining area), she started shouting Mongoose looking in the direction of where he then lived. We all thought she knew my grandfather and was calling out to him. We were wondering how she knew him and asked her. Only then did we realized that she had seen a 'noriya' and that it was called Mongoose in English. You tell me how we can forget the word!"

A desert monitor lizard or 'gho'

Prosopis julliflora is an invasive plant that was initially air sprayed by a government initiative for providing livelihood to the local people. The hope was that the people would burn the wood and make charcoal (koyla) that they can sell. The entire landscape is now overrun with Prosopis and RAMBLE has some projects looking at the effects of the plant on the area.

A truck transporting local koyla or charcoal from the Prosopis

A Spiny-tailed Lizard mom with half her dozen babies

I am told that the Asiatic Wild Ass that the Ranns of Kutch are famous for are not seen in Banni.

Woman at Work

It had taken a couple of days for the camera mounting posts to be ready and I made quick progress after that, setting seven up over one evening and morning session only to be stopped in my tracks by the rains. What timing! The lure gets washed off in the rain and is pretty much useless now!

The camera mounts being fabricated in Bhuj

At one of the grids, the camera post had been knocked down by some buffalo during the night. There were a lot of buffalo videos and close-ups in this camera. I ended up shifting the location slightly so that it was facing in a different direction and was slightly away from this track but still fairly close to the center of the grid. The path to the next grid center close to Hodka village was a mess - the area was completely sludge from rains during the night and was pretty much inaccessible. Thankfully, the 4WD (a Bolero Camper) that we use managed to see us through and I checked the camera.

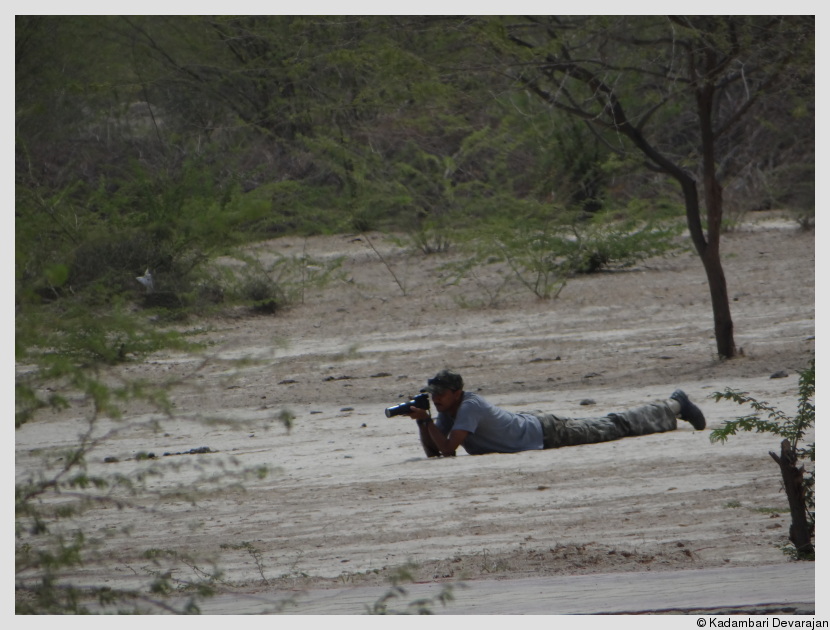

At work (image courtesy - Dr. Pankaj Joshi)

A golden jackal

There was nothing in the camera trap itself but there were jackal pugmarks in two of the trackplots around it. We then left for the Rann after a quick breakfast. On the way to the Rann near Dumado village where we had set up five camera traps the previous day, we saw a monitor lizard (locally called 'gho') and a running fox which the field assistants claimed was a laukdi or Indian Fox - unfortunately could not get a photograph. I thought it was a desert fox - my guess was validated when 15 minutes later we managed to check the first camera trap (grid 17) and found the video of a desert fox ('booey') not very far from where we directly saw the fox earlier.

The desert fox we had seen later

Desert fox pug mark in the post-rain Rann

The field assistants - Rasul Bhai and Mutthalib Bhai

The field assistants had to walk in the muck to retrieve this camera. The area had been transformed into ankle-level sludge. The soil is clayey and 'drank' the first rain - absorbing moisture like multani mitti (Fuller's earth) does. After a few showers, the Rann becomes a 'dariya' or lake and remains so for about four months. This meant that if we didn't retrieve the camera traps set here and the rains continued unabated, we may not be able to fetch them later. After getting the first camera, the field assistants refused to budge and wanted to turn back.

The state of the 4WD after one ride into the muddy Rann

After much prodding by the project coordinator and me, they finally agreed to try and go with me to get the rest. Their apprehension is understandable - it is extremely dangerous to go on the Rann after a rain. The possibility of getting stuck in the middle of nowhere is very daunting.

Me - in the Rann near the village of Dumado

We successfully managed to retrieve ALL the camera traps that had been set in the Rann although none of the rest had any animal videos. It was very dangerous driving through this transformed land and it was a unique experience seeing it metamorphose from dry, parched, salty, white desert one day to sludge the next from overnight rain. On our way back to Hodka, near Auddo village we saw a Chinkara ('haran') and I got a photograph.

Playing hide-and-seek - spot the chinkara!

The chinkara is an elegant and delicate-looking gazelle found in these parts. It is a light tan or buff in color with some dark chestnut or brown-black and white stripes on the face, running from near the ears to the muzzle and a pair of slender horns starting just above the eyes, and before the ears. This one just sprung across the road (very springbok-like in gait) and sprinted across a fair distance in seconds. It stopped behind some Prosopis, turned and looked at the vehicle and I managed a quick picture before it disappeared into the thick prosopis.

After this, things were uneventful except for the fact that the brand new, white 4WD was completely covered in mud and looked quite a sight. The field assistants cleaned it up a bit and removed the large mud debris from the top and windshield of the car. We then went to the RAMBLE field station and they hosed some of the muck of quickly. On our way back to the Bunga, we saw a mongoose ('noriya') - this seemed smaller but plumper than the common grey mongoose and seemed to have some spot-like, unusual markings. The bunga gets unbearably hot and it is a lot more pleasant outdoors with a slight breeze and an overcast sky.

The ship of the desert

I had decided to do some scouting and check other areas out in the region besides Banni. I was told that Narayan Sarovar is far away and Chari-Dandh is inaccessible right now. Dr. Joshi recommended that I go to Dhinodhar instead. So we left directly from the field one morning and went to Dhinodhar via the town of Nirona. The midday sun was sweltering. I have had a midday meal only twice since coming here (roughly a week) - I just feel thirsty and quench it with water, chaas (buttermilk), and some cool drinks. A lot of small shops near roads have big barrels wrapped in wet sacks that people can fill cold water from. The people are warm and friendly, and very curious to see a woman gallivanting in a jeep (and occasionally driving it) studying animals. But I digress.

The route to Dhinodhar was rather uneventful. Nirona is famous for its Rogan work, a form of painting that only a handful of artists (seven, I think) currently work on. Basically, it is an endangered artform, almost on the verge of extinction. This is done on a piece of cloth with special 'paint' made of powdered colored stones mixed with castor oil and a metallic-needle to apply this paint on the cloth. The paint is painstakingly applied on the cloth with the needle to form intricate patterns made up of colored dots of paint. A handkerchief-sized piece of cloth could take up to a month of labor by one person.

Thorn forest near Dhinodhar

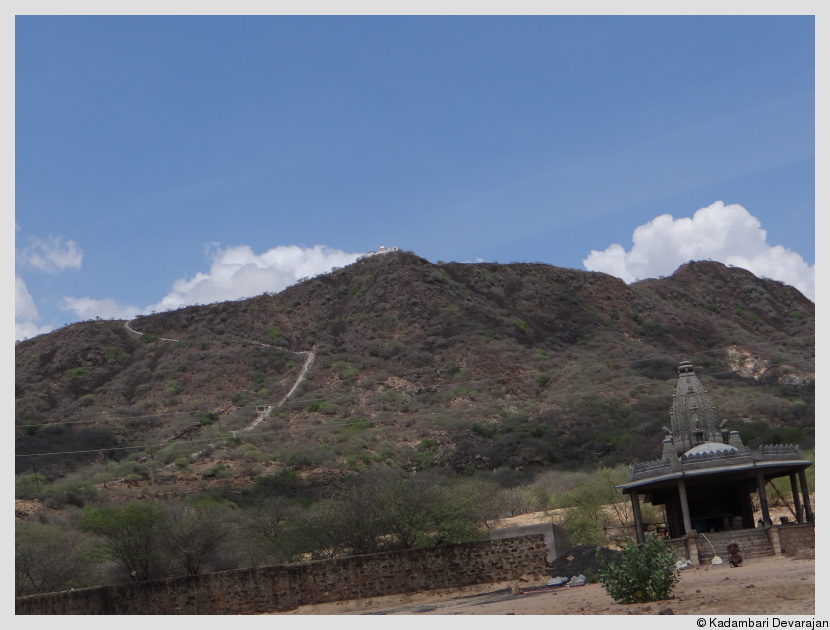

We reached a village near it and met a person who told us that the Fossil Park (we had crossed it without visiting) on the way is definitely worth a visit. He said he used to work there, and also used to work at the Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology. He said he knew the folks at Sahjeevan fairly well, and invited us for lunch. I declined his kind offer and we reached the back side of the Dhinodhar temple.

The temple sits atop the highest hill ('dungar') in the area. Despite its elevation, it was incredibly hot and humid. We went into the short temple entry point which comprised of a few people, who said this was the back side and we had a walk of 3-4 km to reach the temple since no vehicle can go uphill. We went and checked the view out nearby and decided to head to the front (main) entry to the temple. While here, we saw plenty of peafowl and other small birds that I tried photographing without much success.

We visited the Fossil Park which seemed closed but we managed to enter nonetheless and checked everything displayed outside. There were no labels but we could see rocks and stones of various hues (a lovely marine blue, red, yellow, pink, white, etc.). Some had fossil specimens including bones, ammonites, and molluscs.

An Ammonite fossil at the Fossil Park in Dhinodhar

They seem to have a couple of museums (including a geology one) but these were closed and there was no one around, and we decided to not just hang around in the place. We looked around quickly and left. I tried explaining what a fossil is to the field assistants and managed to tell them fairly successfully in Hindi. Saw a jackal, a dead buffalo on which some dogs were feeding, a monitor lizard, a spiny-tailed lizard, a calotes on a waypoint, and a mongoose.

The temple at Dhinodhar

From here, we went close to the town of Nakhatrana, took a turn 14 km before it, and reached the entrance to the temple. From the base, it was a climb of 999 steps to reach the temple. I am not crazy enough to climb all the way up to a temple with 999 steps in the hot, midday sun. I gave it a pass and decided to head back since it was almost evening. On the way to Hodka from here (and Bhuj) there is a point with a hoarding that says that the Tropic of Cancer passes through there. I stopped to take a photo and had to explain to Rasul Bhai and Mutthalib Bhai what the Tropic of Cancer is - rather proud that I managed to do so successfully. I am picking bits and pieces of Gujarati and Kutchi. I know the local names for an assortment of wildlife already. So, yay!

Anil Gohil photographing a spiny-tailed lizard near the RAMBLE field station

We had to retrieve the camera trap from grid 39 - the path was a little muddy and the clean car (Meghji bhai had cleaned it the previous day feeling sorry for its condition - he exclaimed that it's a brand new car and doesn't even have a number plate yet!) was once again splattered with mud but it wasn't as bad as it was in the Rann. There was nothing in it except for a couple of buffaloes. We then returned for a quick breakfast (during which they also cleaned the car a bit) and left for grid 32 on the road to Bhirandiyara. I had set this one under some Prosopis bushes and didn't realize that one of the branches was drooping over the camera. So whenever there was a breeze, the branch would bend lower near the camera and trigger it.

Nilgai in the camera trap that was set

The next morning, I was shocked to see a whopping 146 exposures in a single day and then realized that this is what must have transpired. Oh well, another lesson learnt! Transferred the images and set the camera again. None of the trackplots had any small carnivore pugmarks, but one had nilgai hoofprints - this part seemed to be frequented by nilgai ('roj') since even before setting the camera up we saw some nilgai droppings around. When I checked the videos, the last one had three nilgai come there at 2:27 AM in the night! My first wild herbivores in the camera trap :) Have plenty and more of domestic herbivores - no shortage of buffaloes here!

Birds at Naukhanda Talav - a black-necked stork and a common coot, with a thick-knee running in the foreground!

Spoonbills at Naukhanda Talav

Some birds at Rudramata Dam - flamingoes with painted Storks

I had to leave earlier than planned due to the rains. It was frustrating to go scouting and trying to set camera traps in the rains with most parts becoming inaccessible, and everyone thought it didn't make sense for me to linger.

I was a little disappointed at not staying longer but reassured myself with the thought that I will possibly be returning for a longer stint in a few months. The way back to Bhuj from Hodka was peppered with quick birdwatching stops - at the lovely Naukhanda Talav and the huge Rudramata dam. I can't wait to return in winter when the area would be different and there would be a host of colorful, winged visitors to welcome me :)